Attention conservation notice: 1200+ words about a nearly sixty-year-old paper on the foundations of microeconomics, maliciously re-interpreting it in ways its author explicitly disclaimed, by someone with no qualifications in economics. I wrote this in 2012 or 2013, re-titled in 2014, and never got around to properly finishing it. I dust it off now because I'm in the middle of reading Jason Smith's A Random Physicist Takes on Economics, and see that he had basically the same idea, but said it better and in public. This might, therefore, serve to amplify his message.

I recently re-read Gary Becker's "Irrational Behavior in Economic Theory" paper (Journal of Political Economy 70 (1962): 1--13), and want to talk about it. (Like most of what I know about economics, I was introduced to this paper by my father, many years ago now.) Becker was, to my mind, the embodiment of much of what is wrong with the discipline and practice of economics (see, e.g., John Emerson on Becker's work on families [1, 2]), but this is a genuinely brilliant paper. In many ways, the paper was wiser than its author.

Let me start with the basic observation of the paper. Suppose you have a monthly grocery budget. (Or book budget, or drug budget, or...) This budget, together with the prices of grocery items, dictates what you could buy in the way of groceries. Suppose that the price of onions goes up. Then, just as a matter of arithmetic, the maximum number of onions that you can buy goes down, and for any given level of consuming other goods, you can buy fewer onions. Even if you pick a totally random collection of groceries each week, having a fixed amount of money to spend will ensure that when the price of something go up, you will (on average) buy less of it.

If all the consumers in a market also have budget constraints, then the same reasoning applies to them, too, and so the total quantity of onions bought will tend to fall as their price rises. This is, of course, a basic idea of standard economics, but what Becker shows is that this has nothing to do with satisfying preferences or maximizing utility, or any other assumption about how individuals make decisions. Consumers' could make decisions by lots of different mechanisms --- indeed different consumers could be driven by different mechanisms --- and it wouldn't matter. What does matter is that they all have budget constraints.

Becker's treatment of the producer side of the market is subtly different, and doesn't rely on budget constraints. (Becker indeed insists producers aren't subject to budget constraints, which not only would be news to many small business owners I know, but would also mess up applying his reasoning about consumption to markets for capital goods.) Rather, the the insight is that a wider range of productive techniques, and of scales of production, become profitable at higher prices. This matters, says Becker, because producers cannot keep running losses forever. If they're not running at a loss, though, they can stay in business. So, again without any story about preferences or maximization, as prices rise more firms could produce for the market and stay in it, and as prices fall more firms will be driven out, reducing supply. Again, nothing about individual preferences enters into the argument. Production processes which are physically perfectly feasible but un-profitable get suppressed, because capitalism has institutions to make them go way. If you think this account of producers and supply is all less tidy and satisfactory than the treatment of consumers and demand, I agree with you, but it is, after all, far better than the usual microeconomic account of these matters.

Becker doesn't go in this direction, but of course this completely undermines welfare economics. The whole grasp of that sub-field on reality comes from assuming that individuals' choices reflect their judgments of utility. If that's true, we could read off a lot about people's (subjective) welfare from aggregated market prices and quantities. By breaking the link between microeconomic relations for such aggregated variables and individual utility, Becker breaks the link between observations and welfare economics.

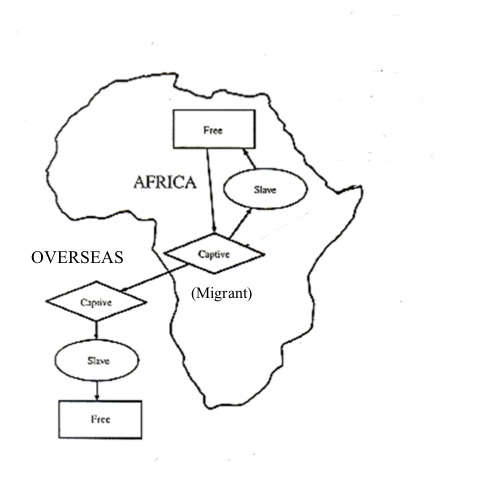

Going further, Becker also removes the link between positive microeconomics, at the level of the market, and individual behavior. Though Becker doesn't put it this way, and would have been horrified by the thought, his argument is it really doesn't matter how individuals make decisions, or even whether economic behavior is usefully thought of as "making decisions" at all. Rather, everything depends on the constraints put on behavior by institutions. That consumers have budgets and can't spend more than that, and that producers can't keep running at a loss, these are both institutional facts about the social organization of capitalism, not facts about how individuals act. (Of course, institutions have to be implemented through individual actions, institutions aren't some sort of cloud hovering over society telling people what to do, but that's another story.) This implies that there are all sorts of different possible micro-foundations for our positive economics, since anything that preserved the institutions would serve. It also suggests that a different set of institutions would lead to a different positive economics. Since institutions change over space and time, then, positive economics would have to be historically relative.

In short, I am inclined to say that Becker fully deserves his Nobel Prize on the strength of this paper alone. The citation, though, should have read "For exploding the foundations of welfare economics, and re-constituting positive microeconomics on an institutionalist basis".

Now, this is not what Becker thought he was doing. From the opening and closing of the paper, it's clear that what he thought he was defending business-as-usual for the Chicago School. Nowadays, we can say that the assumptions of that school about individual behavior are experimentally refuted; science knows that's no more how humans behave than phlogiston is how stuff burns. Even back then, though, there was a lot of criticism for the lack of realism of these assumptions. For instance, Herbert Simon (pbuh) kept pointing out that human rationality is computationally bounded...

Chicago Schoolers had a range of response to such criticism. One was to ignore it and go ahead with the work. (This is part of why I am leery of "shut up and calculate" responses to conceptual criticisms; they're only as good as the basis for the calculations.) The prize for chutzpah went to Milton Friedman, here as elsewhere a profoundly malign influence, who claimed that this lack of realism was in fact a virtue, and actually what made economics extra scientific. (I am not exaggerating, and outsource further commentary to Simon, 1963.)

Compared to that, Becker must have thought he was holding out an olive branch. Look, he (in effect) said, I'll grant for the sake of argument that we're totally wrong about how people make decisions. At the market level, it wouldn't matter, things would still come out the way we say they should. So why not let us hold to those assumptions, just to have something definite to work with?

But of course this won't do. Whatever you feel about Occam's Razor, "This assumption is superfluous, therefore it should be retained" is a very strange rule of method. (Why not assume that people maximize utility, and that utility is purple?) A more sensible reaction to Becker's own argument would surely be to avoid relying on those assumptions for anything, at least until he could provide some independent support for them.

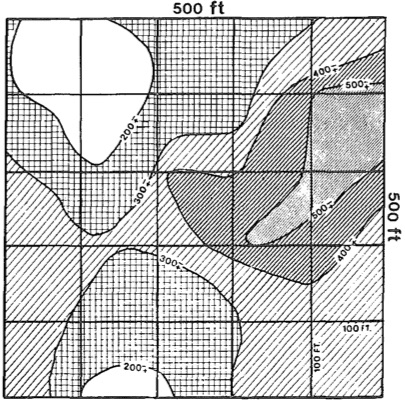

On a more constructive note, I suspect there is a connection to be made here with John Sutton's "bounds approach" to studying industrial organization, where the aim isn't to solve for the equilibrium of the one true model, but instead to find relationships, generally inequalities, which hold across a broad range of models. There might even be some sort of analogy to thermodynamics, which is what you get for nearly-any system built out of molecules when its parts can only interact through a restricted set of collective degrees of freedom (viz., exchange of heat, pressures, a few chemical species, etc.). But both of those would call for real thought and original work on my part, rather than mildly-malicious exposition.